How Tragedy and a Russian Forged the World’s Best Lifeguard Department

By: William Lobdell

In the fall of 1913, the well-to-do Frost family traveled from their home in Hollywood to spend a month in the new resort community of Corona del Mar, staying at the 30-room Hotel del Mar on the bluffs overlooking the ocean and Newport Harbor.

On a Friday morning, Dr. Lowell C. Frost jumped on a ferry from the then-standing Corona del Mar pier inside the harbor to Balboa to buy groceries. His 29-year-old wife, Margaret, took their two young children onto the long-since-demolished oceanside Corona del Mar pier, which extended into the ocean in line with what’s now Marguerite Avenue (it was called Pier Avenue back then).

The main attraction was the high surf, which grew especially fearsome at the entrance of the harbor (this was before the jetties). Somehow, Margaret’s four-year-old son, Lowell Jr., fell from the pier into the roiling ocean. His mom, a strong swimmer, quickly instructed her three-year-old daughter to go find help and then leapt into the sea, likely wearing a long dress and maybe even heavy shoes.

Margaret grabbed her son and tried to swim to shore. But the powerful current and waves swept the pair toward the menacing harbor entrance. The turbulent white water ripped Lowell from her grasp, and both disappeared under the water.

Margaret’s lifeless body was found just outside of the surfline. Rescuers never recovered the remains of Lowell Jr.

Two months later, a grieving Dr. Frost presented the City of Newport Beach with a resuscitation device called a Draeger’s pulmotor, the world’s artificial respiration device, in hopes of preventing another tragedy. Dr. Frost’s inscription on the case paid tribute to his wife “who with clear eyes unhesitatingly faced and met death in the unavailing attempt to save the life of our son.”

The gift in 1913 sparked the formation of the Frost Life Saving Corps, which was composed of Newport Beach firefighters. The primitive lifeguard operation had three major drawbacks: 1) The firefighters could barely swim; 2) The city had virtually no rescue equipment like paddle boards or dories (it instead relied on cork ring buoys with lines attached that were placed in a few spots along the oceanfront); and 3) The 1910s resuscitation equipment mostly didn’t work, and, even when it did, only the fire chief, A.W. Jackson, knew how to operate it.

For a decade, this well-intentioned “lifesaving” corps bumbled along, understaffed, undertrained and ill-equipped. The frequent drownings continued. But then, a Russian-born meteorologist named Antar “Tony” Deraga came along and single-handedly remade Newport Beach lifeguarding into one of the most elite units in the world–a distinction it still retains today.

When Tony Deraga arrived in Newport Beach in 1919 to set up a weather station for the County of Orange, few would have predicted this self-taught meteorologist would turn out to be one of the more fascinating and influential characters in Newport Beach history.

Deraga was brilliant, affable, innovative, handsome and tanned (many news stories mentioned this; it seemed to be important at the time). More importantly to this story, Deraga was a strong swimmer, comfortable in large surf, and the only man in town who knew the Shafer Prone Method of resuscitation (a forerunner to CPR). It was a skill he learned during the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars in a Russian Red Cross unit.

Working at his weather station in a small house he and his wife, Martha, rented on the bluffs of Corona del Mar, Deraga quickly became one of the best meteorologists in the country, keeping on the cutting edge of technology. For instance, his passion for the ocean led him to champion the building of a marine weather and ocean conditions station on the Balboa Pier, and his love for aviation drove him to be one of the first to use weather balloons to more accurately forecast weather conditions for pilots.

From his perch above the harbor, Deraga observed more than the weather. He witnessed scores of boats capsizing in the harbor’s treacherous entrance and their occupants–many of them nonswimmers–being thrown overboard. It was such a frequent occurrence that Deraga stored a dory in Pirate’s Cove near the harbor mouth. When he spotted someone in trouble, he’d run down the stairs that led from his house to Pirate’s Cover, launch the dory, and row out to the victims, some of whom he’d have to resuscitate. Other times, he’d arrive too late.

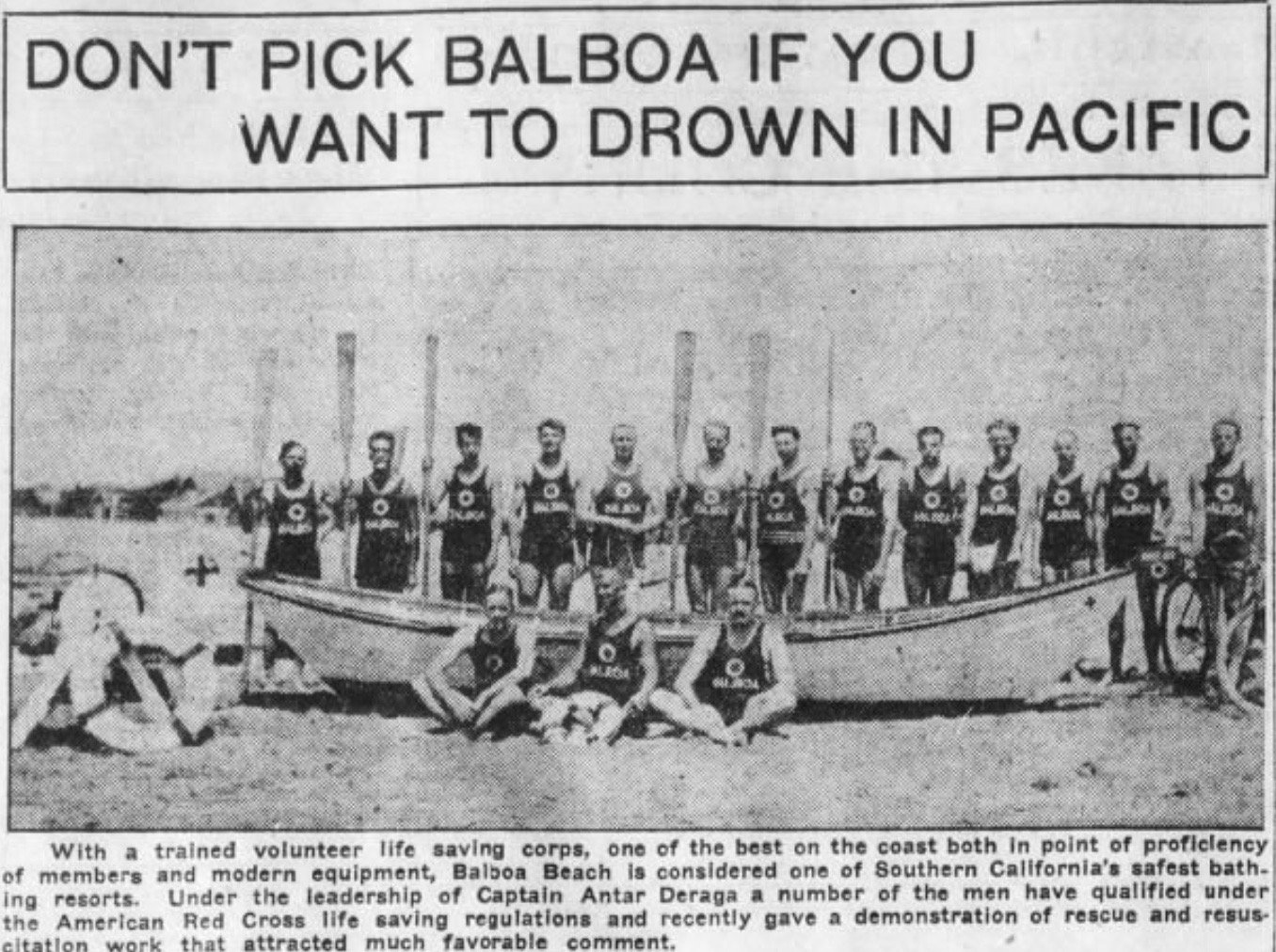

On New Year’s Day in 1923, another boat capsized at the harbor entrance, and all three aboard drowned. Deraga and his wife, Martha, also a strong swimmer, tried to revive the victims but failed. After that, Deraga had seen enough. He set out to form Newport Beach’s first city-funded lifeguard department, featuring guards who could actually swim in the surf. After eight months of planning and lobbying, the City Council approved Deraga’s plan. The department’s original name was the Balboa Red Cross Life Saving Corps, and Deraga named himself captain. It was a good choice.

With $584.50 (about $10,600 today) in the corps coffers, Deraga set up lifeguard stations at Corona del Mar and near the Balboa Pier; positioned a rescue boat inside the harbor mouth; trained more than 20 guards (most of them volunteers) who first had to pass swim, run and first-aid tests; placed warning signs (in English and Spanish) at what was then the most dangerous swimming spots (Corona del Mar, the Wedge, 15th, 16th and 19th streets); ordered a custom-built Cape Cod dory for $120 (it lasted two years before being splintered in the surf); and armed his guards with lifesaving equipment such as copper-cylinder buoys and first-aid supplies. The lifeguards used their own bikes to pedal to the scene of rescues.

In the department’s first year, no one drowned under the lifeguards’ watch, a remarkable feat considering the city’s long track record for drownings.

Like most visionaries, Deraga also had some crazy ideas that haven’t stood the test of time. An avid aviator, he put lifeguards on the wing of a biplane (no kidding), flew low over the water, and had them leap into the ocean next to drowning victims. He used small cannons to shoot coils of rope toward swimmers in trouble. And he believed most beachgoers needed to be rescued because they had just eaten and their full stomachs limited their swimming ability (this was an odd theory my dad and others of his generation strictly adhered to; no swimming until 30 minutes after a meal).

One unconventional practice that worked was hiring a female lifeguard named Hilda in 1927, who, now-lost personnel records showed, was an excellent swimmer and lifesaver. This breaking of the gender barrier paved the way for other female guards who were hired during World War II, when most of the young men in Newport Beach were overseas serving their country. Today, women are among the best lifeguards on the beach.

Despite the occasional unorthodoxy, Deraga’s enterprise (renamed Newport Beach Lifeguard Department in 1927) became one of the most admired life saving operations in the world (Deraga was such a global celebrity that he received a gold medal for bravery from the King of England after rescuing and spending 30 minutes resuscitating a Londoner on holiday in Corona del Mar).

After many attempts by other beach towns to poach Deraga, he eventually took a job teaching meteorology at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. Though gone from the city, Deraga had built such a strong foundation and culture of excellence for Newport Beach lifeguarding that his legacy can be seen even 100 years later. Happy centennial, Newport Beach lifeguards!

William Lobdell is an award-winning journalist and host of the local history podcast, “Newport Beach in the Rearview Mirror,” which can be found on Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Subscribe to follow along as he shares some of the most fascinating stories about our beloved town. You can also follow him on Instagram @newport_in_the_rearview_mirror.