The Kitty Hawk of Hang Gliding

By: William Lobdell

On a sunny spring day in 1971, a rag-tag group of adventurers from as far away as San Francisco dragged their homemade hang gliders 600 feet up a Newport Beach hill, turned their rickety flying (a generous adjective there) contraptions around to face the gentle ocean breeze and tried to fly.

The Birdmen, as they called themselves, didn’t soar like latter-day Icaruses, threatening to get too close to the sun. In fact, they didn’t get far off the ground that day—maybe 30 feet for the best of them. But they still made history. It marked the first time the nascent hang-gliding community came together to fly. The day was part Kitty Hawk and part Woodstock, and it marked the beginning of the modern sport of hang gliding.

The get-together was called the Lilienthal Meet because it was held on the 123rd birthday of Otto Lilienthal, a 19th Century German aviation pioneer credited with being the first person to truly fly a glider. Not-so-fun fact about Otto: In 1896, at the age of 48, Otto’s glider stalled and plunged to Earth, breaking his neck. He died the next day.

The meet, which was officially and modestly called the Great Universal Hang Gliding Championships, was expected to attract maybe five hang gliders—that’s how small the sport was at the time. But more than 15 pilots showed up, along with a fun-loving crowd of 300, surprising both organizers and the participants, who until then had felt quite alone in their pursuit of engineless flight. Now, amazingly, they were surrounded by kindred souls.

Event organizers said they picked the launching spot – now known as Spyglass Hill – because it was devoid of fences, had no posted trespassing signs and was blessed with ocean breezes. It was the property of the Pacific View Mortuary and Memorial Park, and the owner soon became aware of this nutty and dangerous event happening on his land without permission. But, apparently not worried about liability (simpler times), he let the flying continue. The hang gliders joked that they were allowed to stay because the cemetery owner thought he might get more business.

And the Pacific View cemetery probably should have gotten additional residents that day. The hang gliders were incredibly primitive, either made by hand or built from a kit. The self-taught builders were engineers, college students studying aerodynamics, tinkerers, and, in one case, a group of sixth-graders supervised by their summer school teacher.

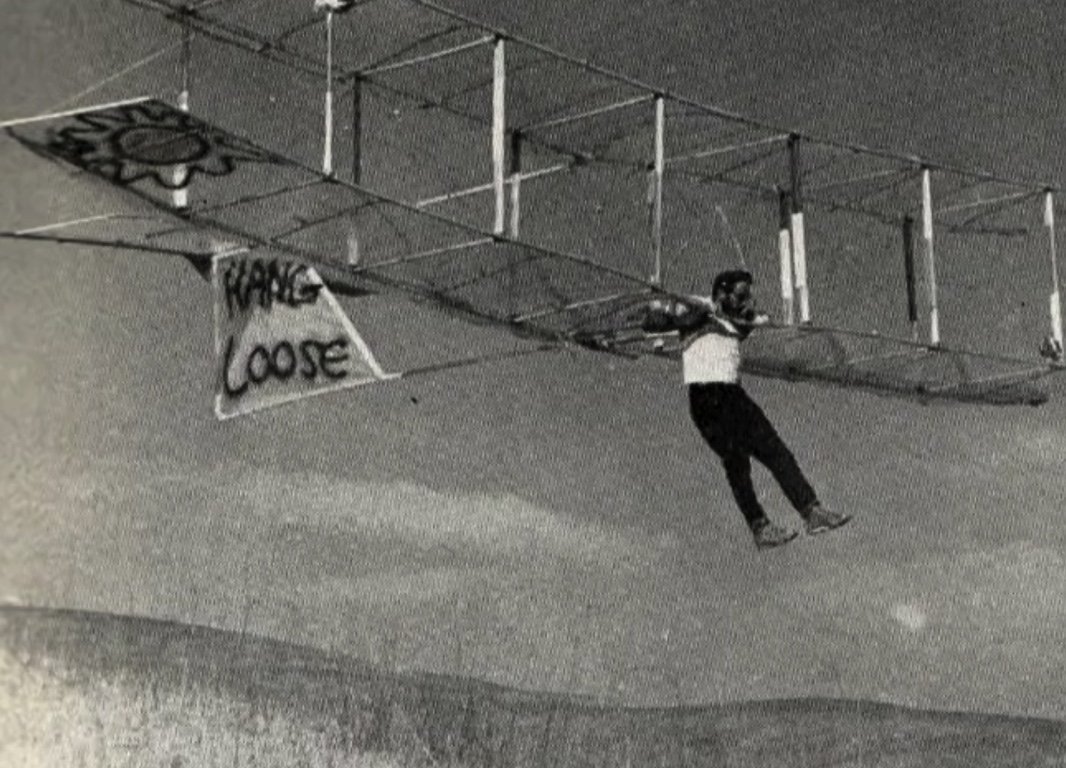

Materials included bamboo, pieces of wood, and, no kidding, repurposed plastic painter tarps. The popular “Hang Loose” model resembled something the Wright Brothers would fly, with two flimsy wings on each side of the pilot, whose legs dangled uselessly below. There were at least two odd-looking hang gliders that attracted a lot of curious attention. They looked like kites, flew better than the rest of the aircraft, and, of course, foreshadowed the design of the modern hang glider.

But most of the gliders could barely fly. The design of them, for the most part, hadn’t changed much since Otto Lilienthal’s time, and Spyglass Hill simply wasn’t steep enough to put much space between the pilot’s feet and Mother Earth.

Some didn’t make it off the ground. Others hopped in the air for a few seconds, like a chicken trying to fly. The best of them climbed maybe 30 feet in the air and covered 600 feet. The longest flight lasted 17 seconds. If that doesn’t sound like much, the Wright Brothers first flight lasted just 12 seconds and went only 180 feet.

It was fortunate that these gliders stayed close to the ground. Even at low altitudes, the uncontrollable aircraft had spectacular crashes. Flimsy gliders snapped in half while in flight. Others cartwheeled across the hillside. Some nosedived into the ground. And the lower wing of one poor pilot’s gilder got caught by an updraft, pushing up the aircraft upward until it stalled and plunged to the hillside from about 15 feet.

For all its historic importance, the Lilienthal Meet would have been lost to history if it weren’t for the presence of journalists from the Los Angeles Times and National Geographic magazine. The Times ran a front page, above-the-fold story and photo the next day headlined, “Time Turns Back as Birdmen Take to Southland Sky.”

National Geographic, which had an international circulation of more than 12 million at the time, ran an 8-page spread about the meet. Spectacular photos dominated the feature story, but the magazine reporter's words were almost as beautiful. After flying in a gilder that day, he wrote in the present tense, “I become a pendulum, swinging under the wing. The ground shoots upward, then steadies. I am neither comfortable nor uncomfortable. I’m just there, like the people standing below me. I feel no fright. For roller-coaster thrills, go to an amusement park. This is something else.”

The media coverage captured the imagination of dreamers around the world who wanted to fly too and sparked the modern, international sport of hang gliding.

You still can find reminders of the Lilienthal Meet in two spots in Newport. One is a historical marker near the basketball court in San Miguel Park at the base of Spyglass Hill. The other is a memorial bench at the Pacific VIew Mortuary and Memorial Park.

The inscription on the cemetery bench reads: “On this hill, May 23, 1971, with a gathering of enthusiasts for personal human flight, began the worldwide sport of hang gliding. May the lift be good and may the joyful spirit of that magical day soar forever.”

William Lobdell, an award-winning journalist, hosts the “Newport Beach in the Rearview Mirror” podcast, which takes a look at the people and events—famous and forgotten—that shaped Newport Beach. The podcast can be found at www.newportbeach-podcast.com, Apple Podcasts and Spotify.